A few years ago, on a mildly windy day, I watched a group of crows line up on the top of a building and then take turns flying off into the draft before letting it gently return them back to the rooftop to do it all over again. This continued for at least ten minutes before I had to bid my feathered friends adieu and go to work. Last summer, I watched two juveniles perch on a cable wire that ran from the power lines down to the ground at a steep incline. While one of the kids was minding its own business the other snuck up and pecked and pulled its sibling’s tail until the sibling lost its balance on the crooked wire and was forced to fly to a higher perch. Then the mischievous, ah hem, ‘pecker’ followed its sibling to the higher perch and started again. And every winter without fail, at least one person will send me the video of the snowboarding Russian hooded crow or the barrel rolling crow or the crows having a snowball fight. Ok, so that last one isn’t real, but with all the other videos of crows at play it certainly seems like it’s only a matter of time before they start hocking little crow-sized snowballs at each other. With all these videos and stories comes the inevitable question: Are corvids having as much fun as it looks like and, if not, what are they doing?

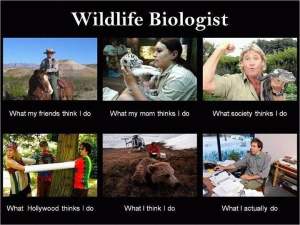

For scientists, this question is inherently difficult to answer. There’s the obvious part where it still remains impossible to ask animals how they feel about their activities, but at an even more fundamental level is the question of: how do we define play? Play, as all things in science do, requires a very specific definition that may or may not depart from how we use the word in everyday language. The most widely referred to definition is the following very dry and jargony sentence: ‘…all motor activity performed postnatally that appears purposeless, in which motor patterns from other contexts may often be used in modified forms or altered sequencing’1. And with that, what I can only imagine must be one of the most fun things on the planet to study suddenly becomes sleep-inducingly boring and the humor of the picture below is no longer confined to biologists.

For now, let’s just focus on the part that said “…activities that appear purposeless.” That leaves scientists with a different problem; how do we define ‘purposeless’ (i.e do you mean right now, or indefinitely? What if it has a purpose but I just don’t know what it is?), and therefore, how do we even identify when animals are playing and when they’re not. Can you see the big circular rabbit hole we’ve gotten ourselves into? Since I think most people use the catch-all definition from Potter Stewart and simply say that you know it when you see it, it can be difficult to empathize with why play has been such a difficult behavior for scientists to say a whole lot about. Now that I hope I’ve given you some insight into why this is a difficult subject to study and thus, in many ways remains mysterious, let’s get to the fun part of talking about what we do know.

For now, let’s just focus on the part that said “…activities that appear purposeless.” That leaves scientists with a different problem; how do we define ‘purposeless’ (i.e do you mean right now, or indefinitely? What if it has a purpose but I just don’t know what it is?), and therefore, how do we even identify when animals are playing and when they’re not. Can you see the big circular rabbit hole we’ve gotten ourselves into? Since I think most people use the catch-all definition from Potter Stewart and simply say that you know it when you see it, it can be difficult to empathize with why play has been such a difficult behavior for scientists to say a whole lot about. Now that I hope I’ve given you some insight into why this is a difficult subject to study and thus, in many ways remains mysterious, let’s get to the fun part of talking about what we do know.

So far, observations of play in birds is limited to corvids, parrots, hornbills and babblers, reaching a grand total of about 25 species2. To put that in perspective, there are ~10,500 species of birds in the world, making it an incredibly rare behavior among birds, and emphasizing the awesomeness of getting to observe it in our own backyards here in the PNW.

Although the snowboarding crow is probably the instance of crow play that gets the most attention, there’s actually 7 kinds of play that researchers have documented3. Maybe I’ll try and publish my observation of the bickering crow kids, but for now, irritating-your-siblings-play is not one of them. Here are the big 7:

- Object play (manipulating things for no reason)

- Play caching (hiding inedible objects)

- Flight play (random aerial acrobatics)

- Bath play (more activity in water than necessary to get clean)

- Sliding down inclines (snowboarding, sledding, body sliding)

- Hanging (hanging off branches but not to obtain food)

- Vocal play (you know how kids go through that phase when they talk to themselves a lot? The crow version of that.)

So what are we to make of seeing ravens hanging, apparently joyfully, from the ends of buoyant branches in our yards or magpies playing tug of war with an otherwise ordinary twig or crows doing elaborate aerial maneuvers for no obvious reason?

Young crows playing tug of war. Photo c/o Bob Armstrong. (The white eye of the bird on the left is not from disease or injury, but is the protective nicitating membrane that many animals have, in case you were wondering.)

Let’s start with the conventional wisdom that everyone grows up hearing: Animals play to practice skills they need to be successful later in life. Cats play with strings to hone attack skills, dogs wrestle to practice fighting skills their wolf ancestors would have needed as adults, etc. The problem with this wisdom is that despite all the intuitive sense it makes it turns out it’s not very…true. In mammals, it has been shown over and over again to be unsupported. In birds it hasn’t been looked at as extensively, and there’s at least one exception I know of that showed ravens play cache (hide things) to evaluate competitors so that they know who is most likely to steal their cache once the stakes are raised and they’re actually hiding food4.

Other then that, the vast majority of data across both birds and mammals have shown that animals who play most often or most fiercely are no better hunters or fighters later in life than their peers. Same goes for the studies that have compared animals that are allowed to play with those who were not5. No difference. So is it as easy as saying crows play just because it’s fun? Well the problem with that is that play can be risky. Playful, distracted kids are often snatched up by predators or accidentally killed by a miscalculation of their environment. With the level of risk that’s involved it seems unlikely it’s not doing anything for them. To make matters more complicated, although animals don’t seem to be better at the skills they appeared to be practicing, some studies show that they do seem to be better off overall. In mammals we’ve seen that they’re more successful parents and have longer life expectancies6. So what might be the adaptive value of fun?

Although there’s still much to be learned as far as testing play in corvids, right now I’m inclined to agree with play researcher Lynda Sharpe, who wrote a piece on this topic for Scientific American which I encourage everyone to check out. Stress is in no way unique to humans, and it can be as debilitating and deadly for animals as it is to us. Play is a great way for animals to hone their stress response so they’re less high strung as adults7. Not to mention the complex, stimulating nature of play helps the brain grow8. So why do crows play? Learning about their peers, gaining new experiences in a low risk way, honing their stress response, and growing their big brains all seem like a good excuse to have a bit of fun to me.

Literature cited

1. Bekoff, M. and Byers, J.A. (1981) A critical reanalysis of the ontogeny of mammalian social and locomotor play. An ethological hornet’s nest. Behavioral Development, The Bielefeld Interdisciplinary Project. pp296-337. Cambridge University Press.

2. Diamond, J, and Bond, A.B. (2003) A comparative analysis of social play in birds. Behaviour 140: 1091-1115

3. Heinrich, B. and Smolker, R. Play in common raves. In: Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative and Ecological Perspectives. Ed: Bekoff, M and Byers, J.A. Cambridge University Press

4. Bugnyar, T., Schwab, C., Schloegl, C., Kortschal, K., and Heinrich, B. (2007). Ravens judge competitors through experience with play caching. Current Biology 17: 1804-1808.

5. Thomas, E. & Schaller, F. 1954. Das Spiel der optisch isolierten Kasper-Hauser-Katze. Naturwissenschaften, 41, 557-558. Reprinted and translated in: Evolution of play behaviour. 1978. (Ed. by D. Muller-Schwarze.) Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross.

6. Cameron, E.Z., Linklater, W.L., Stafford, K.J. & Minot, E.O. 2008. Maternal investment results in better foal condition through increased play behaviour in horses. Animal Behaviour, 76, 1511-1518.

7. Meaney, M.J., Mitchell, J.B., Aitken, D.H. & Bhatnagar, S. 1991. The effects of neonatal handling on the development of the adrenocortical response to stress: implications for neuropathology and cognitive deficits in later life. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 16, 85-103.

8. Ferchmin, P. A. & Eterovic, V. A. 1982. Play stimulated by environmental complexity alters the brain and improves learning abilities in rodents, primates and possibly humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5, 164-165.

Interesting insights on crow behavior! I’m just beginning to discover how fascinating these birds are. Next time I see crows outside, I’ll be watching them to see if I can observe any of those play behaviors!

Thank you Lainey! Enjoy the crows and feel free to come back to me with any future questions you may have regarding your observations.

Wow you gave us the fun of crows. Leave it to me to bring the dark side. You are right it is rare for crow on crow killing. (Twitter today). They are so like us it is scary. Best part is how strong their familes are. My flocks in West Seattle and Renton prove every day this. R

I have a family of crows that I supplement their forage with small snacks (fruit, peanut butter crackers, bits of cheese, superworms ), I’very been doing so for almost two summers now, though this year they’re bringing the fledglings with them, which means I get to watch the not-so-little ones learn. I watched one play with a leaf for 10 minutes, he’d sit on a power line moving it between his feet, then let it drop to the ground, fly down, pick it up, and repeat. I’ve also watched them thwack each other with pine boughs (pull back with beak or foot, wait until sibling isn’t looking and let go). They’re fun to watch.

Aren’t they though? I always have a twinge of pity for folks who see baby crows and just see a noise machine. They have no idea what they’re missing if only they opened their minds an paid a little attention!

This morning I saw a crow killing a crow. Ilooked out the window and saw a shiny black lump on the ground. When I went out, I saw a crow sitting on the ground as if it was sitting in a nest. Its’ eyes were closed and he paid no attention to me. Did not notice if he was breathing. A crow in the tree warned me away. Thought it was a fledging who had fallen so I went inside knowing his family was close by, I watched through the window.. A few minutes later a fawn approached the crow and stopped, sniffing the air around it. Did not touch it. Then quickly walked around it. Then a crow flew down next to it. He started to call loudly, walking around it and vocalizing. Next thing he wrapped his wings around it and started pecking at it picking it up in the process. After a few seconds he threw it down and flew away. I was so fascinated by the actions, I did not notice that about ten feet away, two crows were fighting. They were in the grass beating at each other with wings and beaks. I did not want to see another death so I opened the door and walked toward them, forcing them to fly into the trees. The crows in the trees were screaming. and flying around. Why were they behaving this way?

Hi Cathy, what an interesting account. Crow on crow killings are documented infrequently, and have not been systematically tested (for obvious reasons), so the best us scientists can ever really do for this question is speculate. Crows often fight over things like territory boundaries, food, and mates, which is why it seems like there’s an uptick in aggression during the breeding season when these things are defended more fiercely. Right now, we would expect them to be less aggressive which is why I find your account particularly useful and interesting. Don’t get me wrong, they certainly still fight over boundaries and food year round, but if I had to guess, I think we would find that the number of fights that actually result in death drop during this time of year. As for why these fights either break up or turn deadly, it’s likely due to many factors including the dominance of individuals, their health at the time, the joining of other birds, freak accidents, etc. During these fights both birds are producing a variety of vocalizations that results in the attraction of the crow onlookers you observed. Hope that helps!

The problem was I do not know if the first bird was alive or hurt. He was sitting like he was roosting on the ground. No sound at all. He may have been injured. After the bird attacked him he was lying on the ground, head twisted and wings outstreatched and stiff. He was not fighting back that I could see. Maybe he was already dead when attacked or sick.

Ah, yes that’s a key detail indeed. Crows will certainly attack dying and dead crows so it’s possible that the bird’s death was unrelated (at least initially) to the second individual which later attacked it. Crow expert Kevin McGowen has suggested it’s possible that crows will attack and kill sick or injured crows as a means of predator deterrent (to put it anthroprogenically it’s as if they’re thinking ‘let’s kill this guy before he teaches predators that we’re hunt-able and good to eat!’).

The crows and magpies here in Germany play (?) with pebbles, young and adult alike. They pick them up, hop over to the cobbled part of the driveway leading to the stairs and place them neatly next to each other on a few cobbles. This week 2 jaybirds watched for a few days, then yesterday they picked at the pebbles already placed on the cobbles too. Unfortunately a cat scared them off and they haven’t been back since.

The crows and magpies aren’t fazed by the cats, since anot her will sit in a tree and keep watch, calling when a cat enters the shrubs near the pebbles – then they’ll be off.

In the backyard they all cache acorns. Sometimes the squirrels watch and steal the cache 😉

What a neat anecdote Tina! You should post some pictures of them at work if you have them 🙂

Pingback: What happens to baby crows at the end of summer? | Corvid Research

Pingback: Crows caught play wrestling | Corvid Research

“Ravens . . . to evaluate their competitors. . . once the steaks are raised . . .” I think you meant “stakes” here. Can you still edit the text?

Haha, well a steak on the line would certainly be good motivation to know your competitors! I’ve changed the text, thanks for letting me know Alva!

About 10 years ago I was observing some young crows at play in the restaurant parking lot beside our house. One day, there was a rolled up ball of paper or rags. And to my amazement these fun loving crows started to bat it back and forth across the parking lot to each other – as if playing football. O didn’t have a video camera to hand and smart phones were not as handy in those days, so sadly I have no video of it. Later the same group played king of the castle – a better known crow game.

I have just been watching crows’ antics. To me they were playing. I googled and found your article. I found it very interesting, enlightening – thank you.

You’re welcome!

I have just been watching crows’ antics. To me they were playing. I googled and found your article. I found it very interesting, enlightening – thank you.

I was looking out the window this morning at the strong wind and watching the crows swirling around and making a lot of noise, I am sure they were at play. This is quite a common sight here in Scotland when there is a strong wind.

I’ve seen it with our American crows too!

Just saw 2 young crows playing in my birdbaths. One bath is higher than the other and one of the crows obviously thought it was fun to jump from the higher to the lower and make a splash. Did it again and again and again!

I have a wild raven that has initiating playing with my grandkids age 3 & 4 everyday the last week. But will fly to the top of the roof when any other children or adults come near. Has this behavior ever been reported? It will hop around and follow them as they ride their toys, and has such a fascinating with these two young boys.

That’s adorable. Ravens are HUGE. Your grandkids aren’t scared? We do have ravens near us, but we’re in the city, so they don’t come right up. But the crows sure do, once they trust you.

We’ve been feeding our local crow family every day since March. But we’ve always fed them sometimes so they hang out in our yard. I’ve watched them slide/sled down our shed roof in snow. They seem to play fight over favourite food items; it really doesn’t seem like real fighting. I’ve also taught them to play peekaboo with me. They perch on the edge of the roof over my study and peep down into my window. Then I open the window, and lean out. Each time they peep down again, I say, “Peekaboo!” They seem to really enjoy it and will look right into my eyes. If I make a kiss sound, that will usually prompt them to peep again. They’ll keep playing till even I get bored. I think they’d do it forever. I suppose someone would say they’re just begging for food, but they know when food time is each day, and they know we’ll feed them regardless of whether or not they play peekaboo with us. Seems like just fun to me.

I think in many modern scientists’ noble efforts to want to stay far away from making any animal/human comparisons or cloud their scientific observations with inadvertent personification bias, perhaps this has caused us to ignore the simple but potentially true possibility that a lot of our behaviors may actually have more in common than previously believed with animals. Or at least with species with higher levels of cognition. I mean, who doesn’t want to have fun? Fun is fun whether human, crow, raven or lab rat. And I think we all benefit from having a little fun in our lives.

So yea, I would concur with you and Lynda Sharpe that I think they derive a huge benefit from play, not just for life skills, or even social bonding, but because it just “feels good.”

I certainly feel like I observe this when I watch my neighborhood ravens with their air acrobatics, as they are undeniably enjoying what they’re doing, and will do their antics with their friends, with their mate, with a hawk, with a crow, alone, in a group, they just play, just to play. And they also look like they’re probably expending a lot of energy and taking quite a lot of risk to take part in said play (especially when they pick a hawk as their playmate).

I can’t help but think they are getting a major biological reward for their play. And maybe it’s as simple as a feeling–like that feeling we get when we ride a roller coaster, or when kids beg their parents to take them to Disneyland or watching something that makes us laugh to escape problems life throws at us. Like maybe birds have to have a little fun sometimes too. Life can be stressful for both humans and crows, so perhaps playing and having fun is used for the same reason humans like to have fun.

I guess you’ve seen this one ?

I hadn’t actually!

Pingback: 16 Unnerving Facts About Corvids Most People Don't Know - FactsandHistory