A few years ago, on a mildly windy day, I watched a group of crows line up on the top of a building and then take turns flying off into the draft before letting it gently return them back to the rooftop to do it all over again. This continued for at least ten minutes before I had to bid my feathered friends adieu and go to work. Last summer, I watched two juveniles perch on a cable wire that ran from the power lines down to the ground at a steep incline. While one of the kids was minding its own business the other snuck up and pecked and pulled its sibling’s tail until the sibling lost its balance on the crooked wire and was forced to fly to a higher perch. Then the mischievous, ah hem, ‘pecker’ followed its sibling to the higher perch and started again. And every winter without fail, at least one person will send me the video of the snowboarding Russian hooded crow or the barrel rolling crow or the crows having a snowball fight. Ok, so that last one isn’t real, but with all the other videos of crows at play it certainly seems like it’s only a matter of time before they start hocking little crow-sized snowballs at each other. With all these videos and stories comes the inevitable question: Are corvids having as much fun as it looks like and, if not, what are they doing?

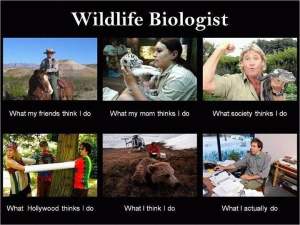

For scientists, this question is inherently difficult to answer. There’s the obvious part where it still remains impossible to ask animals how they feel about their activities, but at an even more fundamental level is the question of: how do we define play? Play, as all things in science do, requires a very specific definition that may or may not depart from how we use the word in everyday language. The most widely referred to definition is the following very dry and jargony sentence: ‘…all motor activity performed postnatally that appears purposeless, in which motor patterns from other contexts may often be used in modified forms or altered sequencing’1. And with that, what I can only imagine must be one of the most fun things on the planet to study suddenly becomes sleep-inducingly boring and the humor of the picture below is no longer confined to biologists.

For now, let’s just focus on the part that said “…activities that appear purposeless.” That leaves scientists with a different problem; how do we define ‘purposeless’ (i.e do you mean right now, or indefinitely? What if it has a purpose but I just don’t know what it is?), and therefore, how do we even identify when animals are playing and when they’re not. Can you see the big circular rabbit hole we’ve gotten ourselves into? Since I think most people use the catch-all definition from Potter Stewart and simply say that you know it when you see it, it can be difficult to empathize with why play has been such a difficult behavior for scientists to say a whole lot about. Now that I hope I’ve given you some insight into why this is a difficult subject to study and thus, in many ways remains mysterious, let’s get to the fun part of talking about what we do know.

For now, let’s just focus on the part that said “…activities that appear purposeless.” That leaves scientists with a different problem; how do we define ‘purposeless’ (i.e do you mean right now, or indefinitely? What if it has a purpose but I just don’t know what it is?), and therefore, how do we even identify when animals are playing and when they’re not. Can you see the big circular rabbit hole we’ve gotten ourselves into? Since I think most people use the catch-all definition from Potter Stewart and simply say that you know it when you see it, it can be difficult to empathize with why play has been such a difficult behavior for scientists to say a whole lot about. Now that I hope I’ve given you some insight into why this is a difficult subject to study and thus, in many ways remains mysterious, let’s get to the fun part of talking about what we do know.

So far, observations of play in birds is limited to corvids, parrots, hornbills and babblers, reaching a grand total of about 25 species2. To put that in perspective, there are ~10,500 species of birds in the world, making it an incredibly rare behavior among birds, and emphasizing the awesomeness of getting to observe it in our own backyards here in the PNW.

Although the snowboarding crow is probably the instance of crow play that gets the most attention, there’s actually 7 kinds of play that researchers have documented3. Maybe I’ll try and publish my observation of the bickering crow kids, but for now, irritating-your-siblings-play is not one of them. Here are the big 7:

- Object play (manipulating things for no reason)

- Play caching (hiding inedible objects)

- Flight play (random aerial acrobatics)

- Bath play (more activity in water than necessary to get clean)

- Sliding down inclines (snowboarding, sledding, body sliding)

- Hanging (hanging off branches but not to obtain food)

- Vocal play (you know how kids go through that phase when they talk to themselves a lot? The crow version of that.)

So what are we to make of seeing ravens hanging, apparently joyfully, from the ends of buoyant branches in our yards or magpies playing tug of war with an otherwise ordinary twig or crows doing elaborate aerial maneuvers for no obvious reason?

Young crows playing tug of war. Photo c/o Bob Armstrong. (The white eye of the bird on the left is not from disease or injury, but is the protective nicitating membrane that many animals have, in case you were wondering.)

Let’s start with the conventional wisdom that everyone grows up hearing: Animals play to practice skills they need to be successful later in life. Cats play with strings to hone attack skills, dogs wrestle to practice fighting skills their wolf ancestors would have needed as adults, etc. The problem with this wisdom is that despite all the intuitive sense it makes it turns out it’s not very…true. In mammals, it has been shown over and over again to be unsupported. In birds it hasn’t been looked at as extensively, and there’s at least one exception I know of that showed ravens play cache (hide things) to evaluate competitors so that they know who is most likely to steal their cache once the stakes are raised and they’re actually hiding food4.

Other then that, the vast majority of data across both birds and mammals have shown that animals who play most often or most fiercely are no better hunters or fighters later in life than their peers. Same goes for the studies that have compared animals that are allowed to play with those who were not5. No difference. So is it as easy as saying crows play just because it’s fun? Well the problem with that is that play can be risky. Playful, distracted kids are often snatched up by predators or accidentally killed by a miscalculation of their environment. With the level of risk that’s involved it seems unlikely it’s not doing anything for them. To make matters more complicated, although animals don’t seem to be better at the skills they appeared to be practicing, some studies show that they do seem to be better off overall. In mammals we’ve seen that they’re more successful parents and have longer life expectancies6. So what might be the adaptive value of fun?

Although there’s still much to be learned as far as testing play in corvids, right now I’m inclined to agree with play researcher Lynda Sharpe, who wrote a piece on this topic for Scientific American which I encourage everyone to check out. Stress is in no way unique to humans, and it can be as debilitating and deadly for animals as it is to us. Play is a great way for animals to hone their stress response so they’re less high strung as adults7. Not to mention the complex, stimulating nature of play helps the brain grow8. So why do crows play? Learning about their peers, gaining new experiences in a low risk way, honing their stress response, and growing their big brains all seem like a good excuse to have a bit of fun to me.

Literature cited

1. Bekoff, M. and Byers, J.A. (1981) A critical reanalysis of the ontogeny of mammalian social and locomotor play. An ethological hornet’s nest. Behavioral Development, The Bielefeld Interdisciplinary Project. pp296-337. Cambridge University Press.

2. Diamond, J, and Bond, A.B. (2003) A comparative analysis of social play in birds. Behaviour 140: 1091-1115

3. Heinrich, B. and Smolker, R. Play in common raves. In: Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative and Ecological Perspectives. Ed: Bekoff, M and Byers, J.A. Cambridge University Press

4. Bugnyar, T., Schwab, C., Schloegl, C., Kortschal, K., and Heinrich, B. (2007). Ravens judge competitors through experience with play caching. Current Biology 17: 1804-1808.

5. Thomas, E. & Schaller, F. 1954. Das Spiel der optisch isolierten Kasper-Hauser-Katze. Naturwissenschaften, 41, 557-558. Reprinted and translated in: Evolution of play behaviour. 1978. (Ed. by D. Muller-Schwarze.) Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross.

6. Cameron, E.Z., Linklater, W.L., Stafford, K.J. & Minot, E.O. 2008. Maternal investment results in better foal condition through increased play behaviour in horses. Animal Behaviour, 76, 1511-1518.

7. Meaney, M.J., Mitchell, J.B., Aitken, D.H. & Bhatnagar, S. 1991. The effects of neonatal handling on the development of the adrenocortical response to stress: implications for neuropathology and cognitive deficits in later life. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 16, 85-103.

8. Ferchmin, P. A. & Eterovic, V. A. 1982. Play stimulated by environmental complexity alters the brain and improves learning abilities in rodents, primates and possibly humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5, 164-165.