Starting in undergrad, my research background has covered a varity of projects, giving me a wide net of ideas and experiences to pull from as I move my corvid research forward. Here is a brief overview of the most fun and important projects that have shaped me as a scientist and citizen. My full CV can be found here: Kaeli Swift 2020 CV

2005-2009 Willamette University: Bachelors of Arts

I received my undergraduate degree from Willamette University in 2009 with a major in biology. As an undergraduate, I participated in independant research projects in a variety of fields including animal physiology, avian field research, and a citizen science driven bird-band resight project. My thesis focused on interspecific recognition between wild crows and friendly humans, which was a spin off of Dr. John Marzluff’s previous work.

After graduating in 2009, I traveled to New South Wales, Australia to participate in a sexual selection study on Satin bowerbirds through the Borgia lab at University of Maryland. The field work was demanding, requiring twice daily data collection on our assigned bowers with only a half day exception once a week. My primary responsibilities were maintaining camera equipment, recording bower data such as quality measurements and number and type of decorations, and conducting 4-hour observation periods to monitor bird activity. Overall it was a great first field experience and exposed me to the fascinating field of sexual selection.

In the off season of 2011 I acted as the museum curator at my Alma Mater, Willamette University. What started off as a side project cleaning drawers out, quickly became a full time 9 month position to recatalog, label and often identify specimens. At the end of the project I was proud to have reorganized the collection into a functioning museum accessible to faculty and the community. It was a great opportunity to give back to my undergraduate institution and explore the different research possibilities natural history museums offer.

Just before entering graduate school I participated in a breeding success survey of Streaked-horned larks in Oregon. This position provided great experience nest searching and working with telemetry units, and furthered my knowledge of using cameras in a field setting. What was perhaps most valuable to me, however, was the opportunity to work with a threatened species and get a sense of the bureaucratic process that goes into getting a species listed.

2012-2018 University of Washington: Master of Science and PhD

Crows, like a number of other animals that includes non-human primates, elephants, dolphins, other corvids, appear to respond strongly once they discover a dead member of their own species. Among these animals the responses can include tactile investigation, communal gathering, vocalizing, sexual behaviors, avoidance or aggression. For people who live or work closely with animals, it’s tempting to anthropomorphize these behaviors based on our opinions of how smart or how emotional we perceive the animals we care about to be.. But as a scientist my job is to separate my personal feelings about animals and use research techniques that allow me to objectively ask questions about animal behavior. By conducting field experiments and employing brain scanning techniques developed by our team, I researched the different ways that crows respond to their dead, what might motivate these responses, and how such behaviors are mediated by the brain. To learn more about these experiments please check out this video or visit the publications page.

2018-2019 PostDoc University of Washington

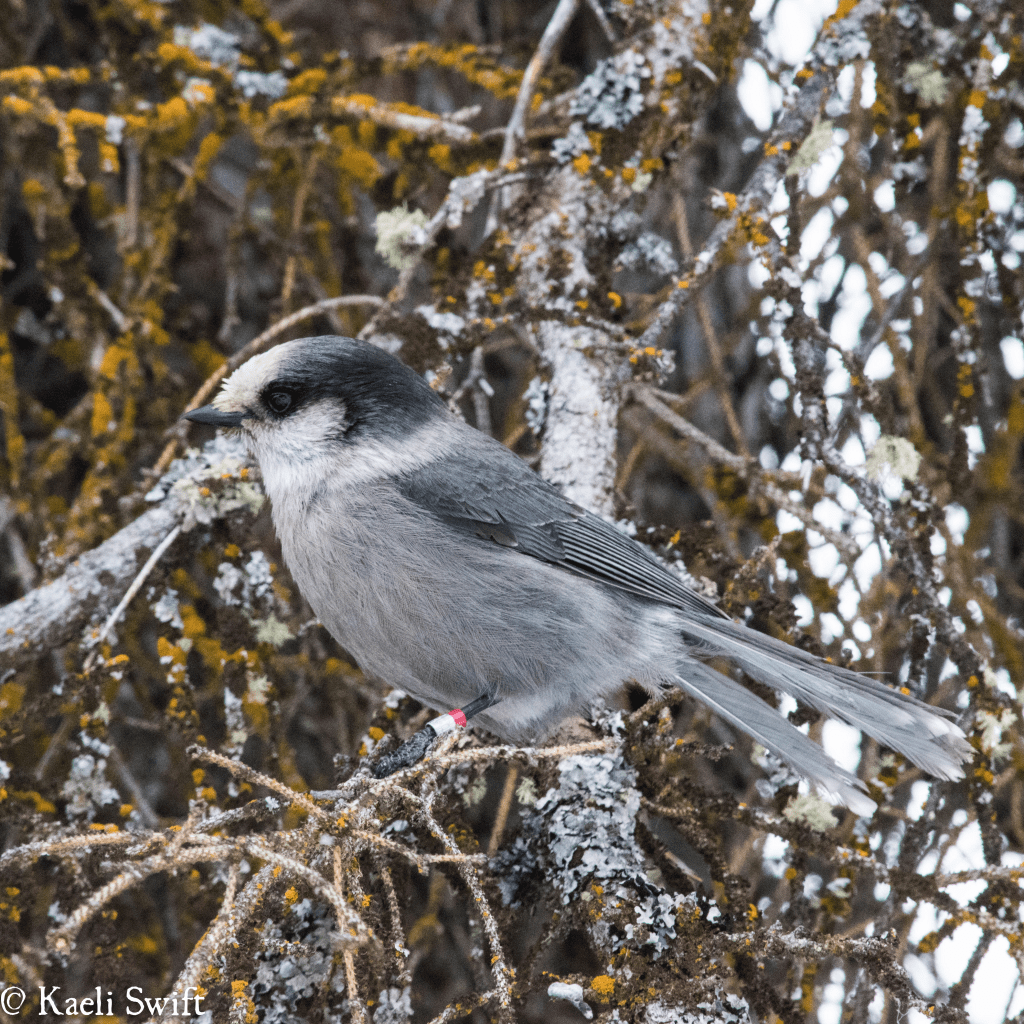

Canada jays, known colloquially as Camp Robbers or Whiskey jacks*, are some of the smallest corvids, weighing in at only 2.5 ounces. Despite their admittedly adorable faces and fragile frames, these are among the toughest animals on the arctic tundra, comprising only a small number of birds that call this area home all year long. To survive the harsh winters, jays depend on food they cache (store) during the fall. Jays start breeding in late February, making them one of the earliest nesting songbirds in this area. Given the blankets of snow still suppressing the fresh fruit and insects they will gorge on come summer, their caches are crucial sources of food during the early breeding period for both adults and nestlings alike.

Sadly, in some parts of their range, jay populations are showing worrying signs of decline. Given that jays cache perishable food, it’s possible that these declines are linked to temperature fluctuations that promote faster degradation of their caches. In other words, the freezer is broken, the food is rotting, and there’s no grocery store with which to restock. With less food during the breeding season, fewer babies will make it to adulthood. If you want to learn more about this issue, check out this video featuring two of Denali’s permanent biologists and my new colleagues, Laura Philips and Emily Williams.

Before we can start getting to the heart of that hypothesis, however, there are fundamental knowledge gaps in the ecology of Denali’s Canada jays that need to be addressed, and that’s where my research comes in. By following and videotaping the foraging behaviors of jays, I hope to establish a better sense of what and where they cache food. With this knowledge in our arsenal, future projects can begin to score the decay of different foods under different temperature regimes or cache locations, relate different caching strategies to reproductive success, and explore many other important questions.

*Whiskey jack is an anglicized version of the indigenous Cree name for these animals, Wisakedjak. Other indigenous nations in the Algonquian language family have similar names.

Hi, I live in the Portland Oregon area. Are looking for volunteer research assistants?

Has anyone ever give you the odd look or vibe when exposing favorite bird as crow/raven?

Yes, lol.

Yes, for sure! Being Norwegian, they are important and good luck birds to us. To my Chinese neighbor, she is very afraid of them as they portend evil.

I have had a flock of crows in Douglas fir in my yard for 18+ years. Suddenly late summer my group quit coming into my yard for their daily peanuts. We always had a friendly relationship, they would call to me when they saw me in kitchen window. I talked to them. They recognized me when I walked nearby. I have been sad that they avoid the yard now. But after reading article on Oregon PBS website I am wondering if you could comment on my thoughts as to why they no longer come. Late summer the crow parents were teaching their 3 offspring how to crack nuts in the street using moving car wheels to run over the nuts. Sadly one day one of the babies was run over. The racket and calling they made caused me to rush outside and see what happened. Our street is rather busy, so we got a shovel and moved the baby to the parking strip and left the body there for a few hours so the family could see it. We then buried the baby away from our home. I realize now that the family stopped coming to the yard after that, no matter how many times I call to them. Do you think our moving the body so soon after death made the family associate it with me? I sure miss my crows.

It’s possible Janet but I don’t think it’s actually that likely. In my experiments I didn’t find that crows moved away from areas associated with dead crows. They were just more wary in them. I wish I could offer you more closure.

Ive been feeding crows peanuts for years here in California and they do know me and call and follow me when I go to get the mail. Not so with other neighbors. Years ago I would ride my bike in the neighborhood and throw peanuts. After a sort period the crows would see me coming and fly toward me. They got to the point where they would fly along side me and ahead of me like the geese in “fly away”. I slowly weaned them off that habit but still give them a snack every day. So, smart and they recognize individuals humans. Crows and ravens are quite impressive.