There are few animals that generate the kind of enthusiasm and following that ravens, crows, magpies and other birds in the corvidae family do. Their presence in our lives is so significant, they appear in the creation stories and fables of nearly all peoples. Today, our love for these birds has given rise to what feels like an entire industry of books, jewelry, artwork, and of course literal fan clubs, some of which serve many tens of thousands of followers. This community is not only fun to be a part of, but is doing important things to improve the reputation of corvids among those individuals or communities who might consider them a nuisance.

There are a couple of common ways though that, in our attempt to uplift corvids, our fandom sometimes trivializes the traditional beliefs of Indigenous North Americans, primarily through cultural appropriation and erasure. If it’s a new or esoteric term to you, cultural appropriation is the act of copying or using the customs and traditions of a particular people or culture, by somebody from another and typically, more dominant people or society.1 Here are three small steps the non-Native community (of which I am a part) can take to more respectfully celebrate our love of corvids, and the people for whom they traditionally hold deep cultural meaning.

#1 Don’t use the term “totem” or “spirit animal,” choose an alternative

In every place and time that humans and corvids co-occur, people have made culturally important meanings, stories, and symbology about these special birds. As a united group of corvid fans, it may therefore be tempting to sample from these practices as a means of creating community. One common way I see this manifest is in the use of terms like spirit animal to describe someone’s connection to a particular corvid. Like animism (the belief that all material possesses agency and a spirit) the term itself appears to have been an invention of anthropologists, but its intent is to refer to Indigenous religious practices. Co-opting this practice as our own, no matter how well-intentioned, devalues cultural traditions that are not ours to claim.

A quick Etsy search of the term demonstrates just how far we’ve allowed the abasement and monetization of this practice by non-Indigenous people (i.e wine is my spirit animal t-shirts.) Even in cases where our use of cultural appropriation doesn’t feel objectively derogatory (it might even feel honorific), its adoption by non-Indigenous people is the kind of cultural cherry picking that has long frustrated Indigenous communities.

“Dear NonNatives: Nothing is your spirit animal. Not a person, place or thing. Nothing is your spirit animal. You do not get one. Spirit animals derive from Anishinaabe and other tribes deeply held religious beliefs. It is a sacred, beloved process that is incredibly secret.”

—Mari Kurisato

To ignore those frustrations and claim that our use of this religious practice is either benign or born out of respect, is to prioritize the needs and feelings of ourselves above those for whom literal and cultural genocide remain contemporary battles. In other words, it’s an act of racism. Of course, Indigenous peoples are not a monolith, and you may find individuals that feel no harm from non-Natives using this term, or even grant you specific access to it (though beware of plastic shamans.) In these cases, I offer that it’s harmless to decline using it despite any special permissions, while adopting it risks hurting and alienating the broader communities for which this or similar terms are sacred.

Fortunately, there are many alternative ways to express kinship with corvids that do not rely on cultural theft. Here are a few of my favorites: muse, soulmate, best friend, fursona, daemon, icon, desired doppelgänger, secret twin, and familiar.

#2 Recognize the diversity of Indigenous nations

Pretty regularly, I see infographics pass through my social media feeds depicting either a photo or some kind of Indigenous-esque looking art and a sound bite about a “Native American” story about crows or ravens. While the intent here is obviously to celebrate a shared love of corvids, the means of doing so makes no effort to actually learn the story or, importantly, from whom that story originates.

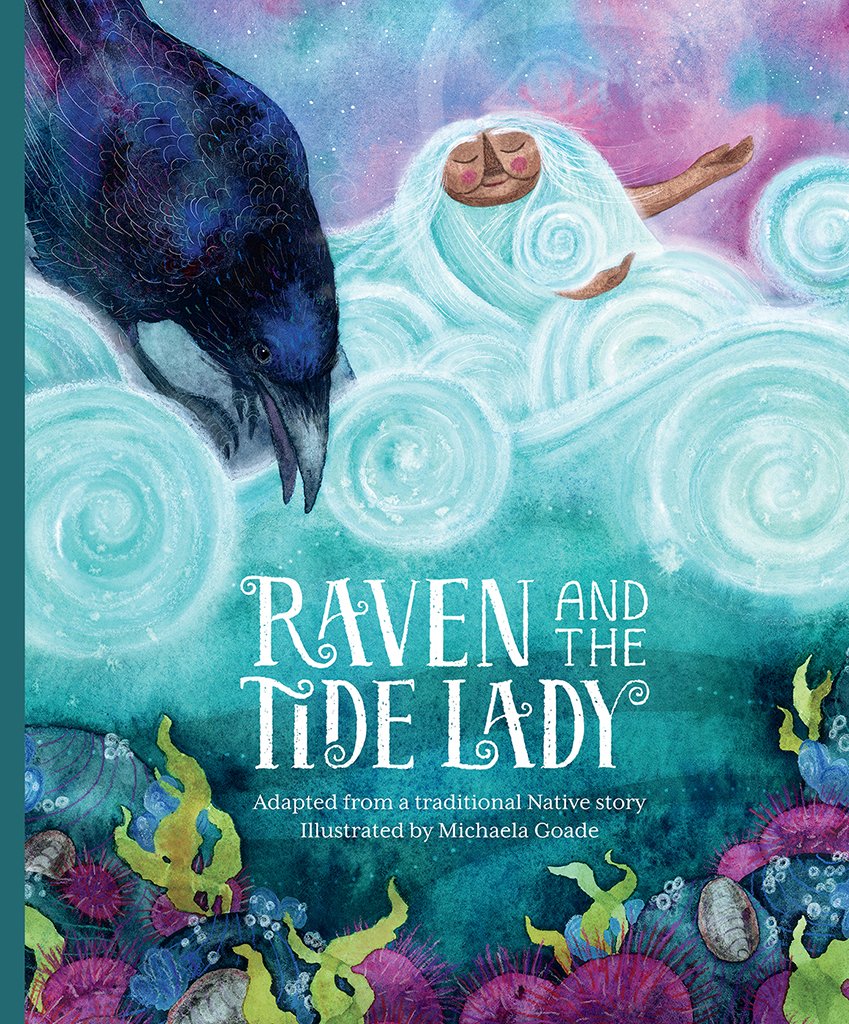

There are 574 federally recognized Indigenous nations in the United States. There are even more when you include non-federally recognized tribes (ex: the Duwamish on whose lands much of the Seattle area is built.) While there is certainly shared knowledge and traditions, it’s important to recognize that these are independent nations with their own creation stories and traditions. For example, the story of Raven stealing the sun to bring light to earth is a Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit legend.2

Attributing them as simply “Native American” stories erases their cultural heritage by treating all Indigenous peoples as a monolith with unified cultural traditions. This is especially pernicious when these stories are told in the past tense, as if the people from whom they originate are gone. Putting in the effort to research where specific stories come from, and how and where that community exists now, is an important step to recognizing and respecting different tribal identities.

For the same reason, another important practice is to research on whose land you currently enjoy the corvids you watch or photograph.

As Larissa Fasthorse explains, “Always know whose land you’re standing on. Who are the original people of that land? You need to find that out. You need to know those people, and, where are they? Are they still there? If not, why? Where have they gone? Start to learn, start to educate yourself. Whose land are you profiting from and how can you start to pay that back in your own way.”

Larissa Fasthorse, interview on Here and Now 10/12/20

So the next time you see an interesting legend about corvids, do some research to learn about the actual people behind that story. Beware of sharing memes that make no effort to do that work. That’s generally a sign that they were not written by someone of that cultural heritage and are more interested in gaining likes and shares than honoring other people. Know on whose ancestral land your corvid watching takes place, and seek out print or digital resources to learn about those people.

While the line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation can be fine, a willingness to seek out knowledge beyond what caught your initial attention is the best way to ensure you’re not engaging in cultural cherry picking. There are several great resources to starting doing this including Whose Land, which is an Indigenous-led project. You can also find more local resources that may serve you better, including the websites of individual tribes.

#3 Buy books and artwork directly from Indigenous sellers

Be it from Navajo, Tlingit, or Haida origins, Indigenous depictions of corvids are unequivocally beautiful. It’s only natural that corvid lovers might wish to enjoy such artistry in jewelry, paintings, sculptures, or books. As long as it’s not in the pursuit of a costume or other forms of identity theft, purchasing and displaying Indigenous art is encouraged, especially when you can use it to draw more attention to the artist. Sadly though, the number of Indigenous creators are far out-numbered by non-Native people looking to profit off their culture.

For example, the Alaska Department of Commerce and Development estimates that 75-80% of what is branded as Native art, was not actually made by Alaska Natives, resulting in the redirection of millions of dollars away from Alaska Native communities.3 So before swiping that credit card, make sure that the creator of that piece has the cultural heritage to claim ownership of it. As the Indigenous led Eighth Generation collective puts it, make sure it was created by “inspired Natives” and was not “Native-inspired.” Don’t be afraid to ask shop owners or gallery curators this question directly. That’s not only an easy way to find out, but it signals to that purveyor that sourcing directly from Indigenous creators is something their customers require. Buying directly from Indigenous artists is an even better option.

Here are a few Indigenous creators and collectives and a slideshow of their products:

Eighth Generation

I-Hos Gallery

B. Yellowtail

Warren Steven Scott

The Shortridge Collection

Seaalaska Heritage Library

As always when buying from artists, expect the price to reflect that the piece supports a livelihood and don’t attempt to barter. The goal shouldn’t be to simply obtain a beautiful object, but to celebrate and support the person who took great care to craft a sharable piece of their identity.

Reconciling the ongoing pain caused by centuries of brutality, land theft, and cultural erasure will not be an easy process. It’s uncomfortable, for example, to realize that while your intent was simply to love on corvids, something you’ve done or said is being called out as anti-Indigenous. But it’s essential that we are willing to engage with that discomfort because it’s through that process that we learn and initiate positive change. Inviting Indigenous voices into your spaces is the most important way to start or continue that effort. Please look for the following individuals who are but a drop in the list of fantastic people you can find. And if you appreciated this article, please consider making a donation to one of the individuals or organizations listed below.

Twitter

Vincent Schilling (@vinceschilling)

Delores Schilling (@DelSchilling)

Jesse Wente (@jessewente)

Mari Kurisato (@wordglass)

Katherine Crocker (@cricketcrocker)

Chief Lady Bird (@chiefladybird)

Daniel Heath Justice (@justicedanielh)

Jay Odjick (@JayOdjick)

Kat Milligan-Myhre (@Napaaqtuk)

Alethea Arnaquq Baril (@Alethea_Aggiuq)

Ruth Hopkins (@Ruth_HHopkins)

Nick Estes (@nickestes)

Kim Tallbear (@KimTallbear)

Kyle White (@kylepowyswhyte)

Ō’m”kaistaaw”kaa•kii (@mariahgladstone)

Indigenous folks in STEM

Plus everyone on this list

Instagram

Indigenous Rising (@indigenousrising)

Corinne Rice (@misscorinne86)

Ryan Young (@Indigenousvengeance)

Indigenous Women Who Hike (@Indigenouswomenhike)

Calina Lawrence (@calinalawrence)

Adrienne Keen (@nativeapprops)

Winona LaDuke (@winonaladuke)

Indian Country Today (@indiancountrytoday)

Tanaya Winder (@Tanayawinder)

Sarain Fox (@sarainfox)

Decolonize Myself (@decolonizemyself)

Organizations/Resources

Reclaim Indigenous Arts

Native Women in the Arts

Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women

Native American Heritage Association

Kituwah Preservation and Education Program

American Indian College Fund

Indigenous Environmental Network

Two-Spirit Resource Directory

Cultural Survival

Many thanks to Liz Landefeld, David Craig, and Vince Schilling for leaving their fingerprints on this article.

Literature cited

1 Cultural Appropriation (2020). In Oxford Online Dictionary https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/cultural-appropriation?q=cultural+appropriation

2 Williams, Maria. How Raven Stole the Sun (Tales of the People). Abbeville Press, 11/20/2000

3 Howell-Zimmer J. 12/2000. Intellectual Property Protection For Alaska Native Arts. Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/intellectual-property-protection-alaska-native-arts

Great post! Thank you.

Erik Zennstrom

So good – thank you, Dr. Swift. Might I recommend a quick edit? Two places where it reads “apart” I think you mean “a part”

Got it, thanks so much!

Excellent! Lots of thought and preparation went into writing this along with a lot of sincerity. Thank you for all of this information.

I am currently thinking that the different nations have so many different contributions that I will never know about all of them. One thing though is that the more we learn, the more respect we have for what the different nations offer.

Thank for all you write, Dr. Swift. I have experienced Corvids as messenger friends. The messages are for me alone and seem to have no cultural vibe. I also have sensed that to think of “bloodline only” whether native other, as the primary relational line, is (for me) limiting. We can choose to enjoy a spiritual lineage, a wider family, where its members are “jumping” in and out of bloodline. That’s my experience. With this awareness, I send my love and appreciation to this wide field of “ancestors”.

Agreed. Spiritual awareness is not dependent on bloodlines. I have no need to borrow a specific cultural/religious group’s language to describe my experiences, so no problem respecting those boundaries but good grief for one group to imagine ownership of some portion of spiritual reality is not reasonable.

I’m with you. Animals are messengers and their wisdom is available to all.

That’s really interesting and, for me, enlightening… I’ll be interested to look at the links you’ve shared and investigate further…I like the way you make people think more deeply x

WADO from an Aniyunwiya lover of koga (crow), and defender of Indigenous existence :~) You rock!

lmao wtf is this preachy nu-left trash? i just wanted to read about birds. unsubscribed.

Bye!

Yep, me too. Only interested in Corvids. You don’t realise this stuff is highly divisive. It does not help Indigenous People. Bye!

Lol, bye!

This comes just as I’ve been thinking about, and trying to understand, why North America and Native Americans are viewed differently than other places: why do people speak of “stolen land”, when everywhere on earth was originally owned by someone else and people have been conquering each other’s land from eternity?

One source I saw last week said the difference is that the two sides didn’t have the same understanding of land and ownership, which I think is true for some Native groups, but not for others.

I’m trying to find sources to help me understand but while the idea that we’re on stolen land is common, I’m not finding explanations of why this is different. Can you suggest any?

Thanks.

Elizabeth

“75-80% of what is branded as Native art, was not actually made by Alaska Natives”

I visited Alaska 5 years ago and very much wanted to bring home a piece of art. In every shop I went, I checked where the art was made and it was never indigenous… I finally found a carving made by a native artist at the museum gift shop, (and he was Canadian). It’s discouraging that profiteering and cultural theft are so rampant.

Thank you for this well researched, well written article. We need to do better about cultural appropriation. I would love to see this piece reach a wider audience; are you planning to publish elsewhere? Perhaps a cultural or arts magazine?

Hi Terry! As it happens, Vince Schilling, who helped me edit this piece, is the Associate editor for Indian Country Today. We are hoping to run it as an op-ed there. Do you have specific suggestions of other places you think it should go?

good reply.

2nd semester, I will be teaching an 8th-grade course about semiotics. With your permission, I would like to use this post as one of the first readings.

Good article, thank you!

I’m thrilled you posted this. Thank you very much.

This is wonderful, thank you for bringing light to this crucial subject and for promoting indigenous artists!

Hello!

Thank you for this. It’s so important to share knowledge.

My sister works at The Native Women’s Hospital in Anchorage, AK as a midwife.

There is a gift shop that is 100% made by natives. Cash only. The hospital also allows native women to sell in the lobby area during the week. Again cash only and it’s 100% legit. So much of the stuff sold around Anchorage is garbage. Clearly with COVID it’s different but just a tip for the future.

Be well!

Enjoy your blog.

Mary Beth

Thank you for this important reminder. The ground we are standing on…

Speaking of Indigenous voices, there’s a beautiful exhibit of Rick Barrie’s work, “Crow Instructions,” at the Froelik Gallery, in Portland.

Here’s the link: https://froelickgallery.com/exhibitions/64-rick-bartow-crow-s-instructions/overview/

i feel that your post is coming from a place of great compassion for our long-suffering native brothers and sisters, who have been subject to terrible depredations since european colonization of their ancestral lands began. this is why it pains me to respectfully disagree. animism is very nearly a human universal! how can you state with such certainty that soul-kinship of a sort with non-human persons like corvidae is reserved only for a certain ethnicity of humanity? is a black person entitled to state they were born in the ‘year of the dragon’, or should they only do so if a certain % or greater of their DNA is han-chinese? surely scandinavian culture has a distinct relationship with ravens.

i understand your frustration with people appropriating other peoples belief systems as a means of projecting their own desires onto animals, but on the other hand, sympathy for non-human sentient life is something precious too

Hi Ravin, this is a really important point, and it’s one that can be easily lost in the fray, so I’m glad you brought it up. The point is NOT that non-Indigenous folks are being asked to reject spiritual ways of knowing the earth and its animals. Indigenous people don’t have “dibs” on that. What’s being asked is that you find ways of doing so that are unique to yourself and your cultural heritage. That’s why if you look back, you’ll see I offered up a whole list of alternative ways to express deep kinship with corvids, including referring to them as your soulmate. I really think Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer (author of Braiding Sweetgrass) put it best during her interview on Ologies with Alie Ward. She was speaking more broadly about traditional ways of knowing a place, but you can just as easily apply it to ways of knowing a specific animal. I’m just going to copy the text for you below and hopefully it will resonate with you as it did for me…

“I think it’s also really important, when we’re avoiding cultural appropriation, to have an authentic experience of engagement with place. You don’t need to say, well, “Native people tell us to be grateful for the gifts of plants around us.” Um, yes, that’s absolutely true, but the way that you manifest that gratitude should be in your own cultural framework. You don’t have to take another way of showing gratitude for the gifts of the earth. You can show it your own way. Coming up with authentic expressions of your own relationship with the living world is a way to make your experiences much more powerful because they’re your own, and it avoids cultural appropriation as well.”

i think it is a testament to the power and reality of native mythology that so many people who do not share the genes of our brothers and sisters can nonetheless acknowledge corvid-kinship when they receive their spirit-eggs. it is a damning testament to humanity and, sadly, to this nation that the peoples that once held dominion over this sacred land are not held in higher esteem and are now virtually ignored politically and culturally.

i think it is only logical that when other humans came to this land they would experience the same things that led native humans to believe what they believed. they would see that corvidae are so different, and yet so like us; so illuminating to the nature of the experience of consciousness, and yet so different and mysteriously so.

i think the best and most respectful approach to the whole-of-the-reality-of-the-problem are measures to ensure the economic and reproductive and family health of native people alive right now. they should be empowered. kulkurkampf is a poisoned dialectic; just look at the pained rejection of so many other commentators. and again i worry about anything that damages human recognition of non-human sapients. humanity is expanding to metastasis on this planet, to a physical and psychic extent that threatens everything that lives on this planet of earth. instead of preaching parochial, ethnically-delimited systems, whatabout evangelicalism?

anyway, my two monetary units. thank you for your blogging and for all you share with us!

-RL

A lot of your readers, I am sure, have nourished their relationship with the corvids since childhoold. I know that I have. And I also don’t think that we need a lecture from the Culture Police about how we do it.

Nowhere in this article was anyone getting called out for “nourishing a relationship with corvids”. But if they way you’re going about that is negatively impacting others, as the three items mentioned in this article are, then yes, it’s time for a gentle lesson in respecting other people. It’s really not difficult to craft a rich personal identify of corvid kinship without perpetuating harm against indigenous people. If that’s something you’re unwilling to do, or feel no obligation to do because you don’t believe indigenous people when they say those actions suck, you can see yourself out of my readership.

Excellent, thank you for this!

Wonderful post and very timely.

Interesting that if someone disagrees with your point of view you simply reply ‘Bye lol’ instead of debating them or defending your assertions (which are highly contentious outside a narrow circle). Also significant that it seems that ‘cultural appropriation’ only works in one direction. I love and respect crows (and indeed all animals) but do not feel that they should be used to make ideological political arguments.

I don’t need to spend my time debating the value of basic human respect (ever) but especially after I’ve already invested my time in writing a thorough article on the topic. If someone’s not open to seeing the ways different facets of their life intersect with one another (say bird watching and racism) then there’s not much more I can do about that beyond what I’ve already laid out. Fortunately, most readers I’ve encountered are interested in growing and doing better by their crow and human communities alike. So I focus on them and bid goodbye to the folks who need more time on their journey towards inclusivity and racial justice.

The original article is wonderful. The comments are fascinating. Symbols are responded to through codes, and paradigms, that may be idiosyncratic or cultural. The comments here fall into those two camps. Beyond that I will not go. Let others draw the inference.

Please do some more research, because many cultures worldwide have spirit animals and animal symbolism, and none of them stole from anyone else. The ancient Celts, for example. Same with things like cornrows. Vikings braided their hair like that too.

Again. The point is to ground your spiritual connection to animals in ways that reflect your own heritage. If you have Celtic heratige, then reflect on your Fetch. If you’re Norse reflect on your Fylgja. While all these concepts share similarities they have key differences. For example, seeing a Fylgia in life was a sign of impending death, while in other cultures a spirit guide may be physically present at various times. In my experience, it’s the people doing the least amount of research that say things like you did, because it shows how little they care to actually understand beyond the most watered down version of what these concepts meant to the people that invented them.

As for cornrows. That term was literally invented by black slaves because of how the hair looked like the lines of crops they were being brutalized to farm. So no, Norse people quite specifically did not have cornrows. That you used that term with so much indifference to its meaning and unique history should perhaps give you pause as to other places in your life where you might be exhibiting similar levels of unearned claim and authority. As to whether the vikings wore plaits or braids, there’s not a historian alive that can confirm that these were styles worn by the vikings because there are no surviving paintings, despite what someone might have learned from watching How to Train your Dragon. So perhaps maybe you should do some more research?

“The” Native Americans? Which tribe or nation? Lol. The story is Raven stole the moon from a box and flew away with it. When he flew through the smoke hole of the longhouse, it turned his feathers black. Never heard any story of raven bringing us a burning branch. Why you making things up?