For two birds that are surprisingly far apart on the family tree, American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and common ravens (Corvus corax) can be awfully hard to distinguish, especially if you rarely see both together. But with the right tools and a little practice you can most certainly develop the skill. Fortunately, there are many different types of clues you can use to tell one from the other, so feel free to use the links to skip around to what interests you.

Physical Differences

Although crows and ravens are superficially quite similar, there are variety of features that can be used to tell one from the other. Overall size can be a good place to start. This especially helpful if you live in an area where they overlap, but even if you don’t, I find that people who are used to seeing crows take notice when they see a raven in person because it feels ~aggressively~ large. That’s because ravens, by mass, are about twice the size of an American crow.

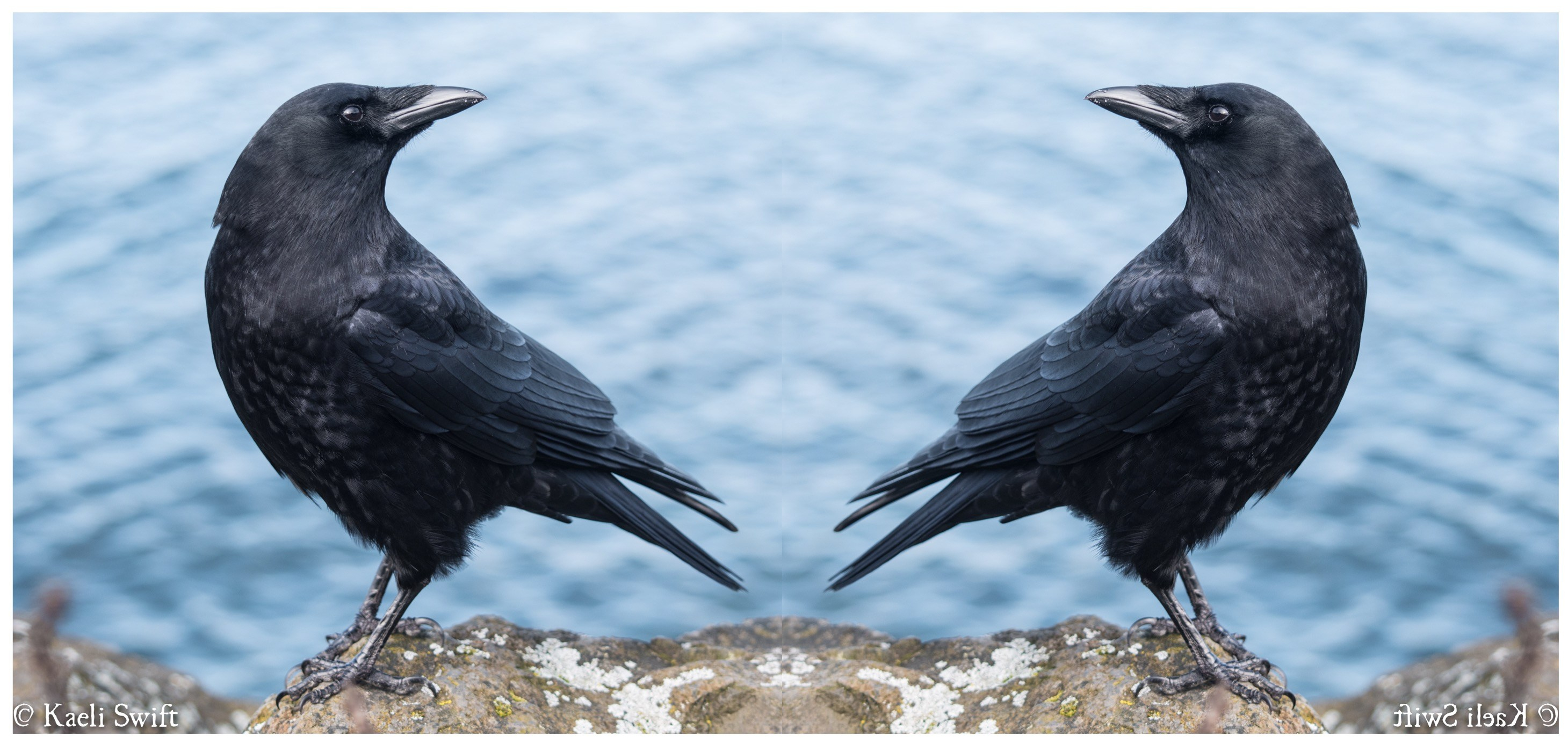

A common raven specimen (top) with an American crow specimen (bottom). On average, ravens are about twice as big as crows, but individually there are certainly large crows and diminutive ravens.

This size difference becomes most obvious is when you look at their face. Raven’s are much more adapted for consuming carrion than crows are (crows cannot break through the skin of a squirrel) and their bills give the distinct impression that they could, in fact, pluck your eyes from your face with little effort. So if your sense of things is that you’re looking at a bill with a bird attached, then you’re probably looking at a raven, not a crow.

With practice, judging the proportion of crows’ and ravens’ features, like bill size, becomes easier.

With practice, judging relative size becomes easier and more reliable, but for a beginner it may not be useful because it’s so subjective. Instead, it’s easier to look at the field marks (birder speak for distinctive features) which provide more objective clues.

With practice, judging relative size becomes easier and more reliable, but for a beginner it may not be useful because it’s so subjective. Instead, it’s easier to look at the field marks (birder speak for distinctive features) which provide more objective clues.

When looking at perched birds, the most helpful attribute is to look at the throat. Ravens have elongated throat feathers called hackles, which they can articulate for a variety of behavioral displays. Crows meanwhile have smooth, almost hair like throat feathers typical of other songbirds.

Even when the feathers are relaxed, the textural differences between the two species throat feathers are apparent. Note that in this photo, the crown feathers of the crow are erect, while the raven’s is not. The difference in crown shape should not therefor be judged in this comparison.

When vocalizing or displaying the raven’s hackles become especially obvious.

In addition to the hackles, ravens can also articulate some of their other facial feathers in way crows cannot. During threat displays for example, ravens will fluff out both the throat hackles and their “ear” tufts.

For birds in flight, however, it’s often difficult—if not impossible—to clearly see the throat feathers. Fortunately, the tail offers a reliable field mark in this case. Whereas crows have a more squared or rounded tail (depending on how much they’ve fanned the feathers) a raven’s tail will have a distinct wedge shape. Additionally, although they are a bit more subtle, there are also some differences in the primary wing feathers. While both birds have 10 primary feathers, in flight, ravens will look like they have four main “finger” feathers while crows will appear to have five. Ravens also have more slender, pointed primaries relative to crows.

Vocal differences

With a little practice American crows and common ravens can easily be distinguished by their calls. The call of a raven can be best described as a deep, hollow croak. Crows on the other hand, caw. Of course, they can both make at dozens of other sounds including rattles, knocks, coos, clicks, and imitations. With practice even these can be recognized by species, but that level of detail is not necessary for most identification purposes.

Common raven call (Recording by Davyd Betchkal-Denali National Preserve, Alaska)

Juvenile common raven yell (Recording by Antonio Xeira-Chippewa County, Michigan)

Common raven water sound (Recording by Niels Krabbe-Galley Bay, British Columbia)

American crow call (Recording by David Vander Pluym-King County, Wasington)

American crow juvenile begging call (Recording by Jonathon Jongsma Minneapolis, Minnesota)

American crow rattle (Recording by Thomas Magarian-Portland, Oregon)

American crow wow call (Recording by Loma Pendergraft King County, Washington)

American crow scolding (Recording by Kaeli Swift-King County Washington)

Geographic/habitat differences

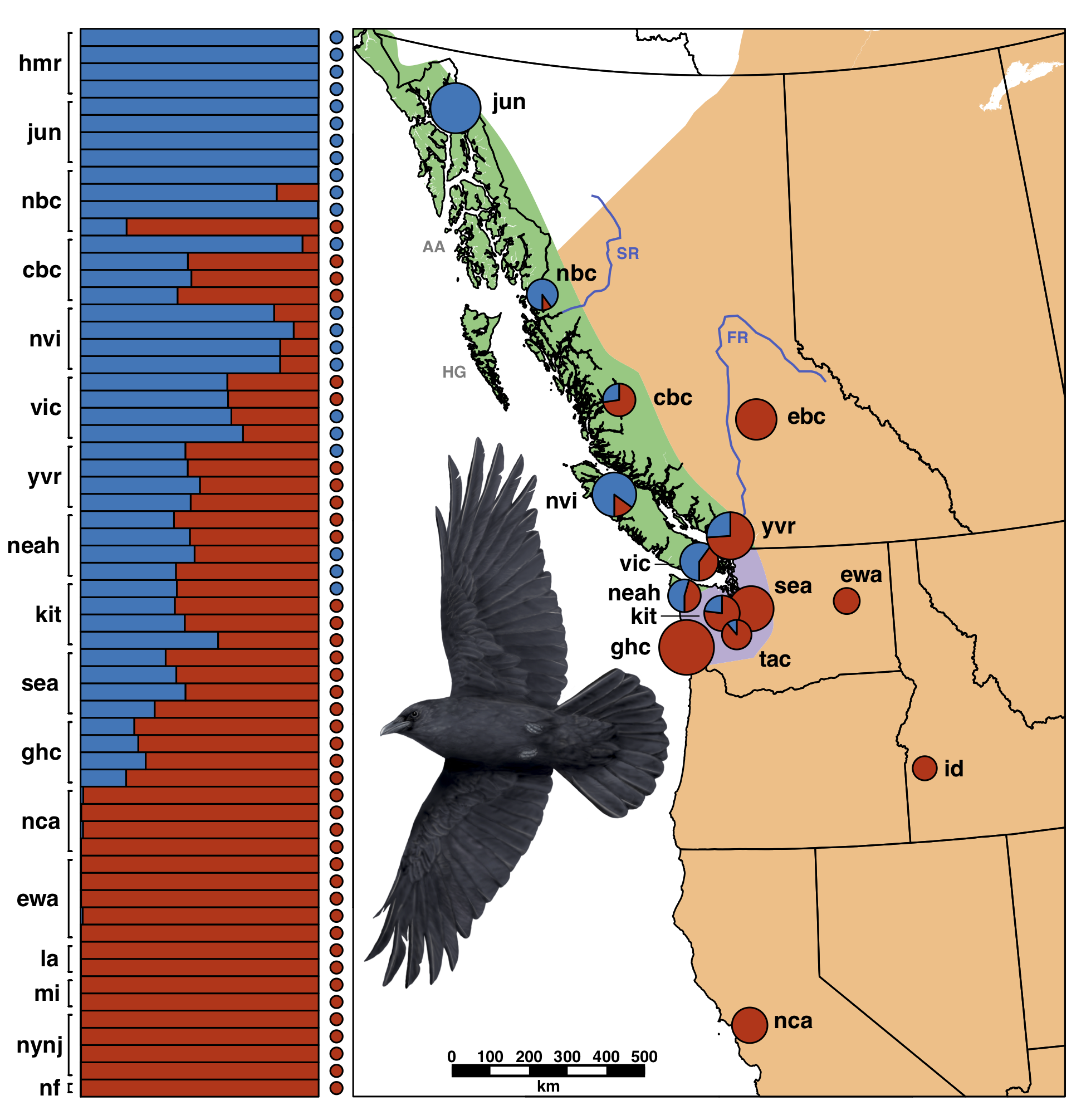

While both American crows and common ravens have wide distributions across North America, there are some key differences in where you are likely to find them. The most notable difference is that ravens are absent throughout most of the midwest and the southeast. Crows on the other hand, occupy most American states with the exception of the southwestern part of the country. The below maps from Cornell’s All About Birds website offer more specific breakdowns (hover over the images to see the caption). Comparing them globally, common ravens range throughout the northern hemisphere, whereas American crows are limited to the North American continent.

Common raven range map

American crow range

With respect to habitat, both birds are considered generalists, with ravens erring more towards what one might describe as an “extreme generalist”. Ravens can be found along the coast, grasslands, mountains (even high altitude mountains), forests, deserts, Arctic ice floes, and human settlements including agricultural areas, small rural towns, urban cities (particularly in California) and near campgrounds, roads, highways and transfer stations. Crows meanwhile are more firm in their requirement of a combo of open feeding areas, scattered trees, and forest edges. They generally avoid continuous forest, preferring to remain close to human settlements including rural and agricultural areas, cities, suburbs, transfer stations, and golf courses. In cases where roads or rivers provide access, however, they can be found at high elevation campgrounds.

Behavioral differences

There are books that could be (and have been) written on this subject alone, so we will limit ourselves to what is likely to be most essential for identification purposes.

Migration

While common ravens are residents wherever they are found, American crows are what’s called a “partially migratory species” because some populations migrate while others do not. Most notably, the northern populations of crows that occupy central Canada during the summer breeding season, travel south to the interior United States once the snow-pack precludes typical feeding behaviors

Breeding

Although trios of ravens are not uncommon, and there have been observations of young from previous years remaining at the nest, ravens are not considered cooperative breeders. Crows are considered cooperative breeders across their entire range (though specific rates vary across populations and not much is known about migratory populations). If helpers are present they typically have between 1-3. So if a nest is very busy with more than two birds contributing to nest construction, feeding nestlings, or nest defense, it’s more than likely a crow’s nest, not a raven’s.

Common raven eggs left | American crow eggs right

Diet

Although both species consume a host of invertebrates, crows consume a larger proportion of inverts and garbage relative to ravens. Mammals, especially from carrion, meanwhile make up the largest proportion of a raven’s diet across surveyed populations. Access to refuse and population location, however, can dramatically shift the dietary preferences of both these omnivores.

Flight

Because ravens consume a lot more carrion, which is unpredictable in its availability and location, they spend a great deal more soaring than crows do. So if you see a black bird cruising the sky for more than a few seconds, it’s most likely a raven. Ravens are also unique from crows in that they barrel roll to advertise their territory. So if you see a barrel rolling bird, there’s a better chance it’s a raven.

Interactions

In places where they do overlap, interactions between the two are often antagonistic, with crows acting as the primary aggressors in conflicts. Ravens will depredate crow nests if given the chance.

A raven defends itself from a crow by rolling upside down. Someday I’ll get a better photograph…

Genetic differences

Throughout most of our history, we have used external cues like appearance, voice and behavior, to sort one kind of animal from another. Now that we have access to a plethora of genetic tools, however, we can ask a new level of the question “what’s the difference between an American crow and a common raven.”

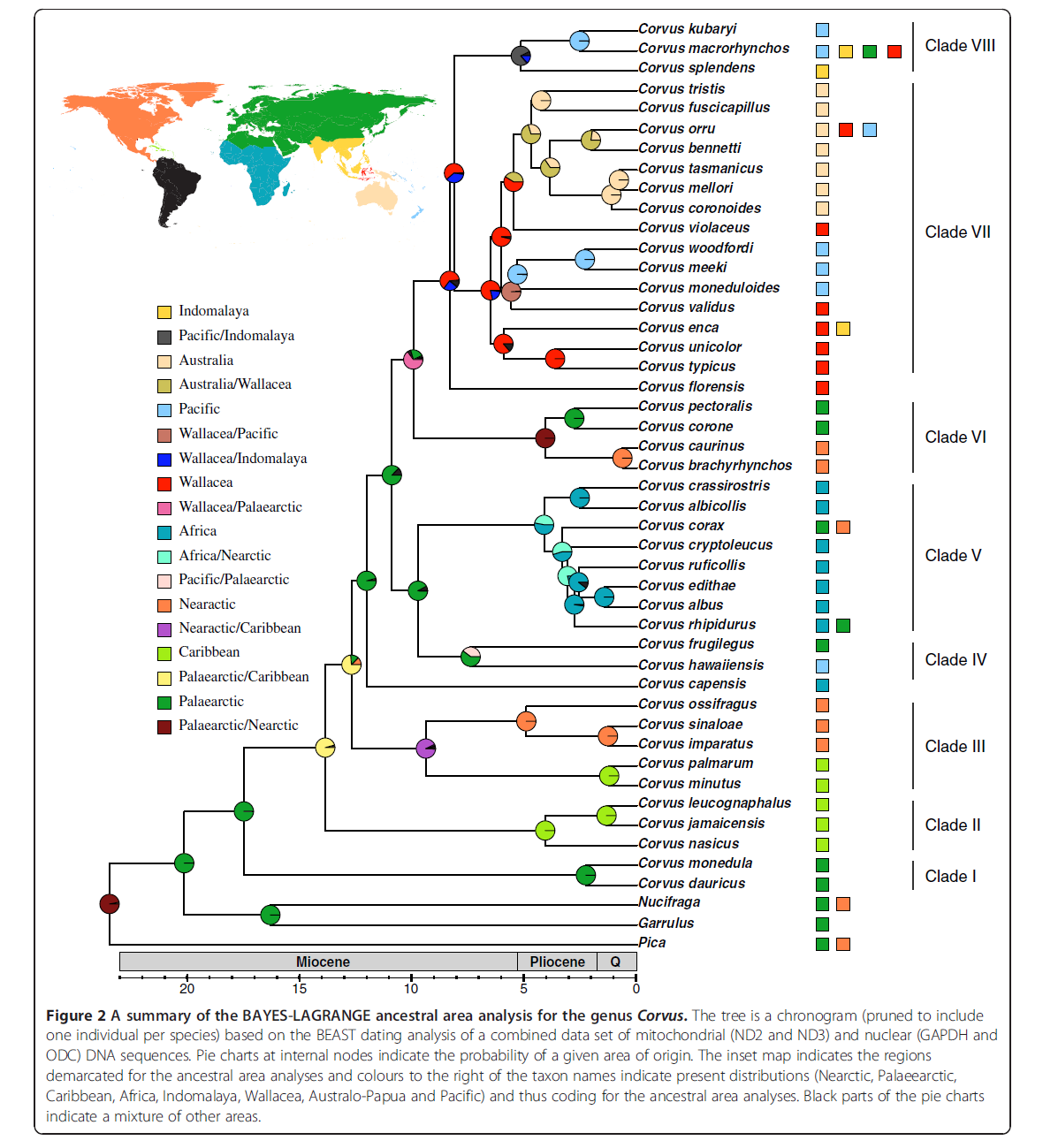

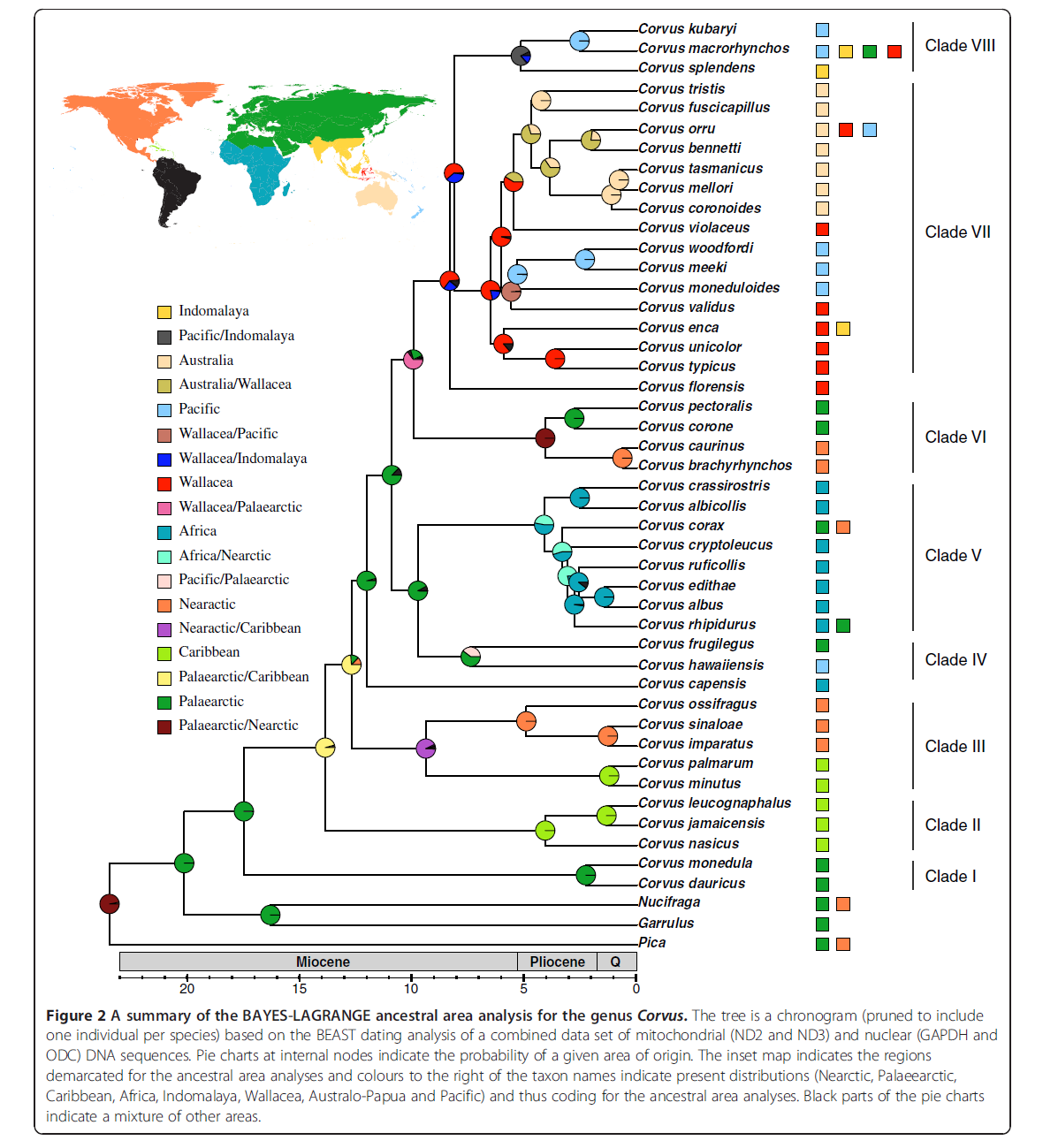

To put it simply, American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and common ravens (Corvus corax) are different species in the same genus, just like lions (Panthera leo) and tigers (Panthera tigris). Species and genus refer to different levels of the taxonomic tree, where species represents the smallest whole unit we classify organisms. The issue of species can get complicated quickly, however, so I’ll direct you here if you want to learn what a mess it really is. Most important thing to appreciate now, is that if you want a quick, back of the envelope way to evaluate if two animals are closely related, look at the first part of their latin binomial (scientific) name. If they share that part then they’re in the same genus (ex: crows and ravens belong to the genus Corvus). If they don’t (ex: American crow is Corvus brachyrhynchos and the Steller’s jay is Cyanocitta stelleri) then they are more distantly related.

Within the Corvus genus, however, there is still a ton of evolutionary space available. In fact, to find the closest shared relative of common ravens and American crows you’d need to go back approximately 7 millions years. Although they are more visually distinct and don’t overlap geographically, American crows are more closely related to the collard crows of China, or the carrion crows of Europe, than they are to common ravens.

Image from Jønsson et al. 2012

Laws and protections

US laws

In the United States, both American crows and common ravens are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. This means that, like with nearly all native birds species, you cannot kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, transport, or export these birds, or their parts, eggs, and nests, except under the terms of a valid Federal permit. It is this law that prohibits the average person from keeping these birds as pets, and requires that rescued crows be turned over to a licensed professional. The MBTA also prohibits the civilian hunting of ravens under any circumstance. Under 50 CFR 20.133, however states are granted an exception for crows, wherein with some restrictions, states can designate regulated hunting seasons.

In addition, under 50 CFR 21.43 of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, you can also kill crows without a license and outside of the regulated hunting season if they are in the act of depredating crops, endangered species, or causing a variety of other destructive issues. You can obtain the specifics of the Depredation Order here. Such lethal control must be reported to Fish and Wildlife to remain within the law. No such depredation exceptions exist for ravens.

Canadian laws

In contrast to the US, no corvids receive federal protections in Canada. Crows and ravens may receive provincial protections, however.

Concluding thoughts

Before we pack it up, I want to leave you with one last useful piece of information. This whole article was dedicated to the question of how American crows are different from common ravens. Hopefully, you’re walking a way with a solid understanding that these animals are in fact different morphologically, behaviorally, and genetically. Asking if American crows are different from common ravens is a different question, though, than asking if “crows” are different than “ravens”. Because while that first answer is a hard, “yes,” there is no one thing that initially classifies a bird as either a type of raven or a type of crow. Generally ravens are bigger and have those elongated throat feathers, but there are plenty of crow named birds that could have been named raven and vice versa. So proceed cautiously and consider the specific types of birds the question’s author is referring to before offering specific answers.

If you want to continue to hone your skills I invite you to play #CrowOrNo with me every week on twitter, Instragram and facebook, all at the @corvidresearch handle. While it’s not to quite this level of detail, I promise it will help advance your ID skills and introduce to to more of the world’s fantastic corvids. For a head start, keep this charming and informative guide illustrated by Rosemary Mosco of Bird and Moon comics handy!

Reference literature

Jønsson K.A., Fabre P.H., and Irestedt, M. (2012). Brains, tools innovations and biogeography in crows and ravens. BCM Evolutionary Biology 12

https://bmcevolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2148-12-72

Freeman B.G. and Miller, E.T. (2018). Why do crows attack ravens? The roles of predation threat, resource competition, and social behavior. The Auk 135: 857-867

Verbeek, N. A. and C. Caffrey (2020). American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Boarman, W. I. and B. Heinrich (2020). Common Raven (Corvus corax), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

With practice, judging relative size becomes easier and more reliable, but for a beginner it may not be useful because it’s so subjective. Instead, it’s easier to look at the field marks (birder speak for distinctive features) which provide more objective clues.

With practice, judging relative size becomes easier and more reliable, but for a beginner it may not be useful because it’s so subjective. Instead, it’s easier to look at the field marks (birder speak for distinctive features) which provide more objective clues.